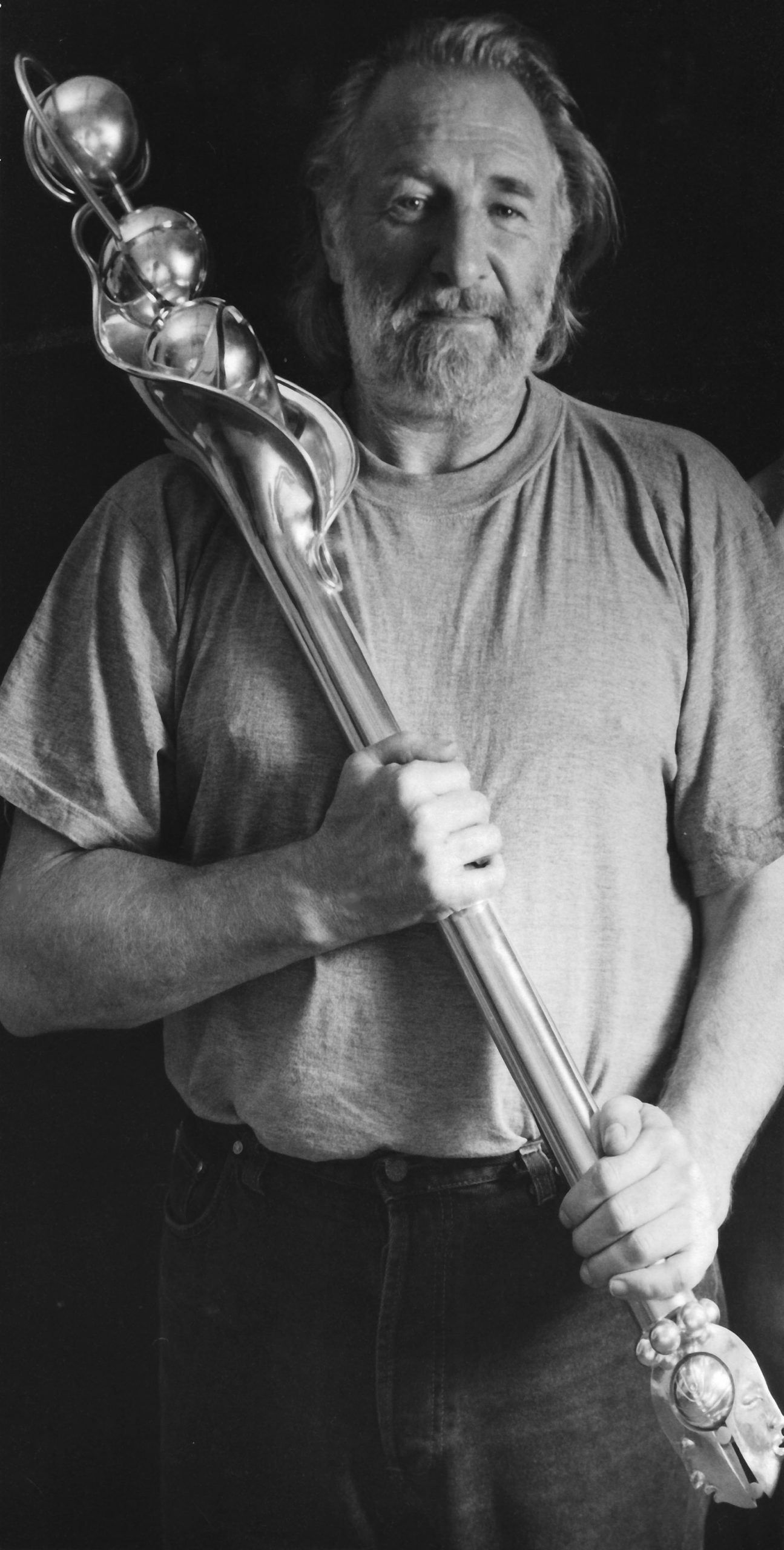

Tom Lomax

sculptor

-

painter.

About tOM

Seeing more dimensions – in colour

Tom started his working career as an apprentice engineer in the construction of locomotives and aircraft. At the age of twenty five he decided to realise his lifelong ambition to make art. He studied painting at Central School of Art and Design and after graduating he went on to study painting at the Slade School of Fine Art.

The Slade became a central part of his career development, as In 1982 he joined the staff there and continued as a part-time tutor until he retired in 2010.

LATEST NFT ARTWORKS SERIES

The Vision

Artist Statement

The results of my practice have always produced a diversity of output; at the core of this practice is my desire that the fundamentals of process, material and subject are inclusive and interchangeable allowing me to freely facilitate opportunities of expression via the overlapping of the seeming unique and separate conventions of sculpture, painting and print. With this at the center I employ both traditional analogue technologies, while concurrently exploring and developing digital modes. i.e.,

I am equally invigorated when modeling figurative or representational forms using wax, ready for bronze casting, or when manipulating geometrical models in CAD (Computer Aided Design) towards 3D printing or other forms of Digital Manufacture. Parallel to these activities there are numerous times when my subject needs to be addressed by the convention and language of painting. On occasion the seeming separate conventions can reciprocate with each other, influencing the direction of execution, e.g., painting or 2D printing might suggest the kernel of an idea that concludes as a digital sculpture and vice-versa.

SCOPE OF STUDIO PRACTICE

Purchase art works direct from Studio@87

Paintings

2d digital Prints

3D printed polychromic sculpture

Bronze Sculpture

Commissions Concept and realisation

Critical eyes

Perspectives

The 1757 publication of Edmund Burke’s A philosophical Investigation into the Origin of our ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful helped to initiate a radical transformation in human thought. For millennia, artists, writers, philosophers and theologians had sought to articulate those realities they believed lay outside human experience and comprehension. The sublime was the space of gods and ideal forms, made visible in sculptures and paintings that transcended the limits of physical reality and appearances and gave form to the intangible and made visible the invisible. For many, Beauty was the bridge that crossed the divide between the seen and unseen, with the ‘ideals’ of divine proportion glimpsed in beautiful things and beautiful forms.

Burke’s proposal was radically different. Beauty became an aesthetic category, ascribed to a pleasing form. It was seen as the opposite of ugliness rather than a moment of divine revelation or the imitation of a universal ideal. The sublime was no longer an objective reality existing ‘out there’,

but a subjective, interior attitude of the individual; a feeling of terror or incomprehension before the infinite, existing in the mind of the beholder. Paintings by Romantic artists such as Caspar David Friedrich and J.M.W Turner reflected this change. They captured states of mind and revealed the

places that evoked these feelings: vertiginous mountains, dense forests, limitless seas, icebergs and intense storms. But in the end, they could never really capture the sublime’s true formlessness and infinite potential.

In the twentieth century, as western artists moved beyond the imitation of physical form into abstraction, the painting itself became a sublime space, with colour field paintings by Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman drawing the viewer into visual encounters where the gaze gets lost and time stands still. But these works are still concerned with provoking the feeling and eliciting an individual response.

Tom Lomax’s digital paintings and sculptures share many of the characteristics of these abstract encounters with the sublime. They delight, beguile and tease the eye with colour spaces that seem to hover on the boundary between solidity and immateriality. We find ourselves tumbling into

fathomless depths as we trace lines whose solidity melts before our gaze. Edges blur, points disappear, forms expand and contract, prompting our breathing to slow, our pupils to widen in wonder and the edges of our body to dissolve into the space around them. For Lomax’s works not only provoke a response; their lustrous, smooth digital surfaces made up of millions of pixels and pin-pricks of ink make visible that atomic space where the hard edges that seem to both separate and contain are in reality porous, fluid boundaries, and where the material and immaterial world are separated only by a different density of molecules.

Lomax’s fields of colour take us to the space between form and formlessness, the point when the invisible becomes visible and when objective light becomes subjective colour. As a point erupts, a line emerges, a space opens up, a solid form appears, before dissolving back into that anonymous,

insubstantial space of colour where nothing is solid and the gaze falls away. Lomax shows us what was lost after Burke, the space where beauty is not just form, but that moment of emergence when form emerges from the immateriality of the sublime. As his two dimensional paintings become three

dimensional sculptures become two dimensional paintings, we find ourselves drawn into the universe’s atomic dance: that space of sublime encounter on the cusp of being, becoming and dissolution.

The following piece was written some time ago, in response to the sculpture of Tom Lomax.

The new works, mostly digital pieces, are technically very different. They have developed from his primary concern with sculpture, but are informed by both his grasp of and inventiveness with computer technology, a transference

perhaps from the engineering aspect of his approach to making art. And by his new and unexpected use of colour. Wild, imaginative, almost perverse in its use of deeply saturated pigments, this colour is surely a response to the

virtual world so many of us now inhabit. The works substitute the artificiality of screen and digital colour with all its fraudulence and deception for the natural, but by some sleight of hand transform it into something that surprisingly refers to both.

(2) from Tess Jaray’s book, Painting Mystery & Confessions

Perhaps there is no way of using the word maverick, as an adjective if there were then that is how Lomax’s sculpture could be described. It doesn’t fit into ‘mainstream’ it is not of now’, it is not ‘retro’. It doesn’t fit into any obvious category, it is sui generis, But the world and its history through art is not

rejected; on the contrary. Lomax is someone exceptionally open to its workings, whose involvement with how things function, how they appear to us, how they engage us, and how the artist might represent these things, is exceptionally strong. And yet, the sculptures seem to grown out of the cracks od things, to point to origins and mysteries we don’t quite want to face; as though they have been excavated, dragged up from forgotten ground, and remind us of things buried away in our minds, thing that are not seemly to dwell on in this so called scientific age.

Tom Lomax’s new sculptures and pictures enchant me. Dizzyingly colourful, cheeky, seeming impossible, playful. These 2-D and 3-D images can only be imagined in the specific form in which they are realised and brought to life- the intellectual imagination embodied and materialised via a wonderfully permissive digital universe. Michèle Roberts. author, writer, poet and broadcaster